My Journey Through Fuzzing: A Survey of Techniques and Tools

I spent months diving deep into the world of fuzzing for my thesis, fuzzing is a very broad topic that encompasses many techniques, tools, and strategies. Unfortunately, there isn't a single resource that covers everything in depth, so I had to piece together knowledge from various papers, blog posts, courses, opensource projects, and what not.

This blog post is my attempt to summarize my thesis findings in a more digestible format (you can find the full thesis in the resources section). After reading this, you should have a mental model of how fuzzing works, the key techniques involved, and some practical insights from my own experiences.

The Core Insight That Makes Fuzzing Work

Fuzzing is, simply put, throwing random garbage at a program and watching it break. But smart garbage, guided by feedback.

A fuzzer is a tool that automatically generates inputs for a target program, executes it with those inputs, and monitors for crashes, hangs, or other anomalous behavior. The magic happens when the fuzzer learns from each execution and uses that feedback to generate better inputs.

Fuzzers are classified along three dimensions, each representing fundamental trade-offs:

By internal awareness,fuzzers divide into three types:

- Black-box fuzzers operate completely blind to program internals, seeing only inputs and outputs. This makes them fast and simple to deploy, but they struggle to penetrate beyond surface-level code.

- White-box fuzzers employ sophisticated program analysis to deliberately craft inputs that maximize coverage, but they hit computational walls from problems like path explosion.

- Gray-box fuzzers occupy the middle ground, using lightweight instrumentation to observe execution state without the heavy cost of full program analysis.

By input generation method, there are two approaches:

- Generation-based fuzzers rely on formal specifications or grammars that describe valid input structure, letting them produce well-formed test cases that reach deeper code. However, they require significant upfront effort to define input models.

- Mutation-based fuzzers take existing inputs and randomly modify them, trading some effectiveness for the ability to start fuzzing immediately without writing generators.

By exploration strategy, fuzzers split into two camps:

- Coverage-based fuzzers attempt to exercise as much program code as possible through broad exploration.

- Direct fuzzers instead focus their efforts on specific program paths or components for intensive testing.

The dominant approach combines gray-box awareness with mutation-based generation and coverage-based exploration. This combination delivers practical effectiveness without requiring either source code specifications or heavy computational resources.

So now you know that fuzzing is more than just random input generation.

The key is generating a feedback loop that guides random input generation toward interesting program states.

Instrumentation and Coverage Guidance

Gray-box fuzzing works by instrumenting the target program to collect lightweight execution feedback—typically code coverage information. This feedback tells the fuzzer which inputs trigger new code paths, allowing it to prioritize mutations that explore uncharted territory.

AFL++ Instrumentation Example

Think of coverage as a map of where your inputs have taken you. Different coverage metrics provide different levels of detail:

- Block Coverage: is one of the most basic technique and measures how many code blocks have been visited.

- Branch Coverage: the basic unit is the tuple (prev, cur), where prev and cur stand for the previous and current block IDs, respectively.

- N-Gram Branch Coverage: sits between full path coverage and branch coverage. N is the parameter that describes how many previous blocks are taken into account.

- Full Path Coverage: is infeasible, and for a program of n reachable branches, it will require a 2 ^ n test cases while for the branch coverage 2 · n

Different fuzzers make different choices. Vuzzer and Honggfuzz use basic block coverage. AFL uses edge coverage. LibFuzzer supports both. The choice depends on the trade-off between precision and performance—more detailed coverage means more overhead.

The Fuzzing Process

The fuzzer starts with a corpus—a collection of valid or semi-valid inputs (or generated inputs if it's a generation-based fuzzer).

The fuzzer takes one of these inputs and mutates it. The mutations aren't completely random; they're informed by strategies that have proven effective, like flipping individual bits, inserting boundary values like zero or maximum integers, or splicing two inputs together.

┌────────────────────────────────┐

────▶│ Take the first test from the │◀───────────────────┐

│ priority queue │ │

└───────────────┬────────────────┘ │

│ │

▼ │

┌────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ Mutate it and pass it to the │ │

│ target program │ │

└───────────────┬────────────────┘ │

│ │

▼ │

┌─────────────────┐ │

│ │ │

│ Did it increase │ │

│ code coverage? │ │

│ │ │

└────┬──────┬─────┘ │

│ │ │

Yes No │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Reinsert the test case in │ │

│ │ the queue but don't change │─────────┘

│ │ its priority │ │

│ └────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

▼ │

┌────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ Reinsert the test case in the │ │

│ queue and increase its │ │

│ priority │ │

└───────────────┬────────────────┘ │

│ │

▼ │

┌─────────────────┐ │

│ │ │

│ Did it cause │ │

│ a crash? │ │

│ │ │

└────┬──────┬─────┘ │

│ │ │

Yes No │

│ │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌────────────────────────────────┐

│ Save the test case │

│ │

└────────────────────────────────┘

The Roadblocks of Fuzzing

The biggest challenge in fuzzing is dealing with roadblocks—program logic that prevents random mutations from reaching interesting code paths. These roadblocks come in two primary forms: checksums and magic values.

I discovered how severely these roadblocks hinder fuzzing when I started working on a Phasor Data Concentrator implementing the IEEE C37.118 protocol. The protocol has specific structure:

Every frame starts with a sync word (0xAA), followed by frame type information, then a FRAMESIZE field indicating expected byte count, and ends with a CRC checksum.

Consider what happens when you mutate a valid frame: flip a few bits in the payload, and the data changes. But now the checksum is wrong, so the PDC immediately rejects the packet without ever processing the modified data. The fuzzer is stuck at the front door, unable to explore any interesting parsing logic deeper in the code.

This is what researchers call a roadblock. Various techniques have been developed to overcome these obstacles, and I'll show you some of the most effective ones in the following sections.

Sub-instruction profiling: a clever trick

One technique that really clicked for me was sub-instruction profiling. Consider this code that checks for a magic number:

// Original code: requires exact 4-byte match

if (input == 0xDEADBEEF) {

// interesting code that might have bugs

}

The probability of a random mutation hitting exactly 0xDEADBEEF is about one in four billion. The fuzzer could run for years without finding it. But what if we transformed this code at compile time into something like:

// Transformed code: checks each byte separately

if ((input >> 24) == 0xDE) {

if (((input >> 16) & 0xFF) == 0xAD) {

if (((input >> 8) & 0xFF) == 0xBE) {

if ((input & 0xFF) == 0xEF) {

// interesting code

}

}

}

}

Now the fuzzer has a much better chance. When it randomly mutates the first byte to 0xDE, the coverage map shows new code was reached—the first if-statement's true branch. The fuzzer saves that input and keeps mutating it. Eventually, it might stumble upon 0xAD for the second byte, which triggers another new branch, and so on. The probability hasn't changed mathematically, but the feedback signal guides the fuzzer toward the solution.

For example, this transformation happens automatically in AFL++ when you use the laf-intel compiler option.

Input-to-state correspondence: simple yet powerful

The technique that really impressed me during my research was input-to-state correspondence, implemented in a fuzzer called Angora. The insight here is beautifully simple yet powerful.

Most programs don't heavily transform input before using it in comparisons.

The technique works by colorization: insert random bytes into different positions of the input and observe which of those random bytes appear in comparison operands at runtime.

This is lighter-weight than full taint tracking, which would need to track every single operation that touches input bytes. As a result, even inputs that pass through unknown library functions, large data-dependent loops, and floating-point instructions do not significantly reduce the quality of the results.

Input-to-state correspondence and sub-instruction profiling both solve the magic value problem, but they're not the only weapons in the fuzzer's arsenal. Let me briefly cover some other techniques you'll encounter in the literature before we discuss how fuzzers actually execute test cases.

Other Notable Fuzzing Techniques

There are other techniques worth mentioning briefly:

- Taint Analysis tracks how input bytes propagate through the program, allowing the fuzzer to focus mutations on bytes that influence critical comparisons.

- Symbolic Execution explores program paths by treating inputs as symbolic variables, generating constraints that lead to specific branches. However, it struggles with path explosion in complex programs.

- Concolic Execution combines concrete execution with symbolic analysis, running the program with real inputs while also tracking symbolic constraints. This hybrid approach can mitigate some limitations of pure symbolic execution.

Fuzzing modes

We've covered how fuzzers generate inputs and overcome roadblocks, but there's another crucial design decision: how should the fuzzer actually run each test case? This choice dramatically affects both speed and reliability.

Fuzzers execute test cases in three ways, trading speed for stability.

Simple mode spawns a fresh process for each test case. Perfectly stable but slow due to repeated startup overhead.

Fork-server mode initializes once, then forks a copy per test case. Balances speed and stability by avoiding startup costs while maintaining process isolation.

Persistent mode reuses the same process for multiple test cases. Fastest option but risks state corruption causing non-deterministic crashes unless the target perfectly resets between tests.

Most modern fuzzers default to fork-server mode for the best balance. Persistent mode is worth the complexity for performance-critical fuzzing campaigns, but only if you can verify the target properly resets its state.

Now let's look at how instrumentation itself has evolved to become more efficient.

Advanced Instrumentation Techniques: AFL++ LTO an important Improvement

AFL's original approach tracks edge coverage by XORing random location IDs and indexing into a 64KB shared memory map. This causes collisions—over 75% of edges collide in large programs like libtorrent with 260K+ edges. AFL++ LTO fixes this by injecting instrumentation at link time via LLVM passes. Each edge gets a hardcoded, unique shared memory address, eliminating collisions entirely and auto-sizing the map to fit the program's actual edge count.

Compiler sanitizers: essential for effective fuzzing

Compiler sanitizers are runtime instrumentation inserted during compilation that detect bugs which may not cause immediate crashes. Sanitizers are essential for effective fuzzing. They convert silent bugs into immediate crashes, speeding up vulnerability discovery and ensuring deterministic behavior—the same input always produces the same result, making bugs reproducible.

Binary-only fuzzing: when source code isn't available

Everything I've discussed so far assumes you have source code to instrument. But what happens when you're fuzzing closed-source software, proprietary protocols, or legacy systems? This is where binary-only fuzzing enters the picture—and where things get significantly more complicated: instrumentation becomes trickier since you can't modify the source.

Four approaches exist:

- Black-box fuzzing skips coverage entirely. Simple but ineffective for complex vulnerabilities.

- Dynamic binary instrumentation (e.g., QEMU) emulates execution and injects coverage tracking at runtime. Always works but runs 2-5x slower.

- Static binary rewriting patches the binary to add instrumentation before execution. Near-native speed but doesn't always succeed—some binaries can't be reliably rewritten.

- Hardware-based instrumentation (e.g., Intel PT) uses CPU features to trace execution. Performance varies.

Dynamic instrumentation remains the most reliable approach for general binary-only fuzzing.

Dynamic Binary Instrumentation using QEMU

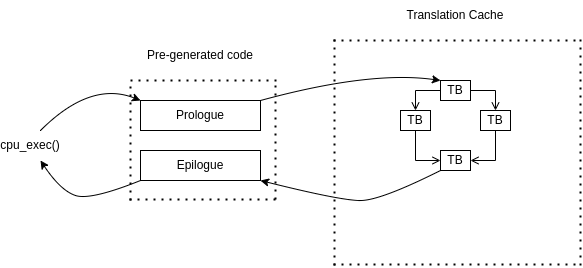

QEMU is an open-source machine emulator and virtualizer that can emulate different CPU architectures. It functions like a JIT compiler but without an interpreter component.

Internal Architecture: QEMU is built around the TCG, which has three parts:

- Frontend: Translates guest architecture code to IR

- Backend: Converts IR to host architecture machine code

- Core: Orchestrates the translation process, manages the translation cache, and handles exceptions

QEMU dynamically translates guest instructions into host instructions up to the next jump or any instruction that modifies CPU state in ways that can't be determined at translation time. These chunks are called translation blocks (TBs), similar to basic blocks. Once translated, TBs are saved in QEMU's translation cache for reuse.

Execution Cycle: QEMU alternates between executing translated blocks and running the TCG. Each TB execution is preceded by a prologue function and followed by an epilogue function. These wrapper functions are fundamental for fuzzing because they can be customized to inject instrumentation and pass coverage information between QEMU and the fuzzer.

Block Chaining Optimization: After a TB executes, QEMU uses the simulated Program Counter and CPU state to find the next TB via hash table lookup. If the next TB is already cached, QEMU patches the current block to jump directly to it instead of returning to the epilogue and main loop. This creates chains of TBs that execute sequentially without overhead, significantly boosting performance closer to native speeds.

This block chaining optimization has been handled differently by fuzzing tools. For a comparison of fuzzers see the thesis in the resources section.

Static Binary Rewriting

Static binary rewriting adds instrumentation by modifying compiled binaries before execution. Three fundamental techniques exist.

- Recompilation attempts to generate intermediate representation from the binary, but requires recovering type information—an unsolved problem.

- Reassembly disassembles the binary, adds instrumentation, then reassembles it. Retrowrite uses this approach to enable AFL fuzzing of binaries, but fails on non-PIE binaries and C++ exceptions.

- Trampolines insert indirection jumps to instrumentation code without changing block sizes. E9Patch uses this technique and works on stripped binaries without needing control-flow recovery. However, trampolines increase code size and add overhead from extra jumps. The tool can fail on edge cases like single-byte instructions or address space constraints.

Static rewriting achieves near-native speed when successful but cannot handle all binaries reliably, unlike dynamic instrumentation which always works at the cost of performance.

So What's the Best Fuzzer?

The answer depends on your goals. As you've seen, fuzzers make a series of trade-offs between speed, effectiveness, and ease of use. Also some fuzzers implement specific techniques not available in others.

In my experience only few of them are mature enough to be used in real-world scenarios.

In the thesis I evaluated with a qualitative analysis the most popular fuzzers available today, for various metrics like ease of use, documentation quality, community support, and more.

For a quantitative analysis I referred to the FuzzBench platform, which is a Google open-source project that provides a standardized environment to benchmark fuzzers across a wide range of targets and can be considered the gold standard for fuzzer evaluation.

Putting Theory Into Practice: Real-World Fuzzing Campaigns

I've covered a lot of theory and techniques. Now let me show you what actually happens when you try to fuzz real software. I conducted two major fuzzing campaigns as part of my thesis, each revealing different challenges and insights.

The first target: one of the most battle-tested web servers in existence.

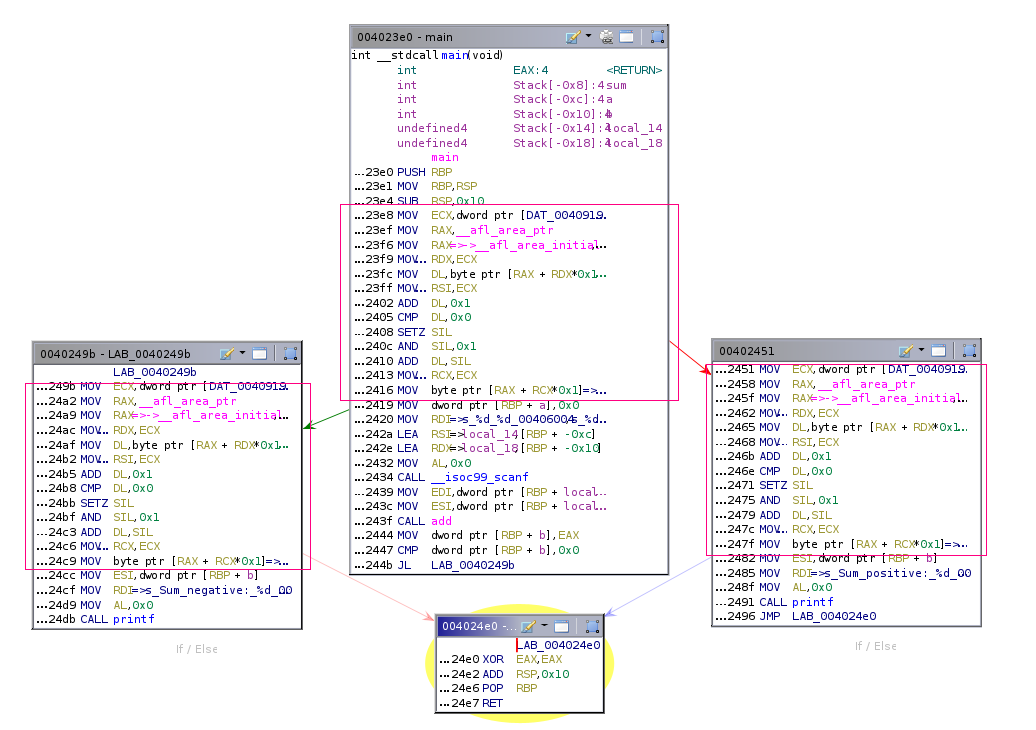

Apache HTTP Server Fuzzing

I chose Apache 2.4.49 as my target—it serves 24.63% of the world's top websites. The main challenge was that Apache expects network input while AFL++ wants to provide stdin or file input. My solution involved modifying Apache's source to forward AFL++ input to a localhost socket, then using Linux namespaces to give each fuzzer instance its own pocket dimension where they could all bind to the same port simultaneously without fighting each other.

I ran 8 parallel AFL++ instances with different configurations (ASAN, MSAN, laf-intel, CmpLog) in persistent mode, limiting each process to 1,000 iterations because too much persistence leads to state corruption. The campaign ran for 8 days on an Intel Core i7-4770 with 32GB RAM and found exactly zero crashes. Apache has been fuzzed so thoroughly by security teams and OSS-Fuzz that finding a bug would be like finding a typo in a dictionary.

As a bonus experiment, I demonstrated detecting CVE-2021-41773, a path traversal vulnerability that doesn't crash. Path traversal bugs are tricky for fuzzers because they're logic errors, not memory corruptions. I used the LD_PRELOAD trick to hook Apache's file access functions (xstat() and writev()), essentially teaching the fuzzer to yell "Hey, that's not allowed!" and trigger an artificial crash whenever Apache tried accessing files outside its base directory.

The Three Approaches I Used for Stateful Protocol Fuzzing

The PDC Case Study

For my second campaign, I worked with a local company to fuzz their in-development Phasor Data Concentrator (PDC)—a component of smart grid infrastructure that collects real-time electrical measurements from power distribution systems.

PDCs communicate using the IEEE C37.118 protocol, a binary format with specific structure: every frame starts with a sync word (0xAA), contains frame type information and a FRAMESIZE field indicating total length, and ends with a CRC-16 checksum. Surprisingly, the protocol includes no built-in authentication or encryption—companies rely entirely on VPNs and network isolation for security. This makes the protocol implementation itself a prime target for vulnerabilities.

I attacked this system from three different angles, each revealing different trade-offs in fuzzing approaches.

Approach 1: AFL++ (Gray-box Fuzzing)

I created a shared library harness that intercepted network calls, feeding AFL++ mutations to the PDC over actual sockets. The setup required modifying the PDC's network initialization code to accept AFL's input, but once running, it proved immediately effective.

Results: Found two vulnerabilities:

- Buffer overflow from unchecked FRAMESIZE field used directly for pointer arithmetic

- Out-of-bounds read from NUM_PMU field used without validation

What fascinated me was how AFL++ got "lucky" in a way that wouldn't work with sanitizers. The OS zeroes memory pages before allocation, so when the PDC read past buffer boundaries into uninitialized memory, it often found zeros. AFL++ stumbled upon mutations producing checksums that matched those zeros, accidentally bypassing validation and exposing deeper bugs. With MemorySanitizer enabled, every out-of-bounds read crashes immediately—paradoxically slowing discovery of the second vulnerability.

Limitations: AFL++ struggled with the protocol's stateful nature. The PDC only accepts Data Frames after receiving valid Configuration Frames first, but setting this up through AFL++ would require extensive source modifications.

Approach 2: Radamsa + PyPMU (Black-box Fuzzing)

I switched to Radamsa, a general-purpose mutation fuzzer, combined with PyPMU—an open-source Python implementation of C37.118. PyPMU handled all the protocol handshaking and state management automatically, letting me fuzz Data Frames that the PDC would actually process.

Results: Found five vulnerabilities total:

- The same two AFL++ discovered

- Use-after-free on uninitialized pointers

- Two state misalignment issues from unexpected frame sequences

Limitations: Radamsa is completely blind to program internals. Most mutations broke the CRC checksum, causing the PDC to reject packets immediately at validation. Simple to deploy but inefficient at reaching code beyond initial checks.

Approach 3: Scapy (Generation-based Fuzzing)

For the most thorough approach, I extended Scapy to fully implement the IEEE C37.118 protocol (code available in my GitHub repository). Scapy lets you define packet structures as typed classes, and crucially, it automatically recalculates checksums and length fields after fuzzing individual fields.

This meant every generated packet had valid structure—bypassing initial validation and reaching actual parsing logic. Scapy also fuzzes intelligently: it knows a ShortField should be tested with boundary values (0, 0xFFFF, -1), while enumerated fields get all valid values plus carefully chosen invalid ones.

Results: The most thorough testing, finding all previous vulnerabilities plus edge cases from boundary value testing.

Limitations: Required the upfront investment of implementing the entire protocol specification—several days of work before fuzzing even began.

The Vulnerabilities: A Pattern Emerges

All discovered vulnerabilities stemmed from the same mundane pattern: missing input validation. The developers trusted FRAMESIZE and NUM_PMU field values from the network and used them directly for:

- Calculating memory offsets

- Determining loop iteration counts

- Sizing buffer operations

When these values didn't match actual packet contents, the PDC happily read past buffer boundaries until hitting unmapped memory and segfaulting.

Not exotic. Not sophisticated. Just classic bounds-checking failures that attackers love and fuzzers excel at finding—exactly the pattern that validates fuzzing's effectiveness against real-world code.

What the FuzzBench Results Taught Me

As part of my research, I examined the FuzzBench platform, which Google created to standardize fuzzer evaluation. One finding really stood out: among the top seven fuzzers, there was no statistically significant performance difference.

Think about that. Years of fuzzing research, dozens of academic papers proposing new techniques, and yet AFL++, Honggfuzz, Entropic, Eclipser, AFLplusplus, and several others all performed essentially the same when tested rigorously across 22 benchmarks with 20 trials each.

This tells me something important about the state of fuzzing research: we're hitting diminishing returns on general-purpose improvements. The low-hanging fruit has been picked. Modern fuzzers have incorporated the key insights—coverage guidance, interesting mutation strategies, handling of roadblocks—and further improvements require specialization.

Where I think the field is heading is toward domain-specific fuzzing. The FuzzBench results suggest we need more targeted approaches rather than trying to build one fuzzer to rule them all.

Where I'd Go Next

If I continued this research, several directions interest me:

First, I'd want to explore differential fuzzing more deeply. Instead of just looking for crashes, you run the same input through multiple implementations of the same protocol or specification and look for discrepancies. This can find semantic bugs that don't cause crashes—like the path traversal vulnerability in Apache that I had to instrument manually to detect.

Second, the problem of fuzzing stateful systems remains largely unsolved. My PDC fuzzing struggled with this—how do you efficiently explore sequences of operations rather than just individual inputs? Some research has looked at grammar-based fuzzing for this, but it's still an open challenge.

Finally, I think there's opportunity in making fuzzing more accessible. The tools have improved dramatically, but you still need significant expertise to fuzz something like a web browser or operating system kernel effectively. Better abstractions, better tooling, and better documentation could democratize fuzzing further.

Conclusion

If I had to distill everything I learned into one insight, it would be this: fuzzing works because most software bugs aren't exotic or subtle—they're mundane mistakes in handling unexpected inputs. Buffer overflows, integer overflows, use-after-free, null pointer dereferences—these are the bugs that fuzzing finds reliably, and these are the bugs that attackers exploit constantly.

We like to think of security vulnerabilities as requiring sophisticated programming errors or deep architectural flaws. But the reality is simpler and more humbling. Most vulnerabilities are just places where a developer didn't validate an input, or made an incorrect assumption about bounds, or forgot to check a return value.

Fuzzing is effective not because it's sophisticated, but because software is fragile in simple, predictable ways. By systematically exploring the space of possible inputs, fuzzing finds the places where our assumptions break down.

That's both encouraging and sobering. Encouraging because it means we have practical tools to find and fix these issues. Sobering because it suggests we're not very good at writing robust software in the first place.

Resources

- A survey of fuzz-testing tools for vulnerability discovery - My full thesis document

- Fuzzing101 - Funny and beginner-friendly presentation on fuzzing concepts (In Italian)

- Forked Scapy with IEEE C37.118 support - My extended Scapy library for fuzzing IEEE C37.118 protocol (see c37.118 branch)

This article is licensed under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license.